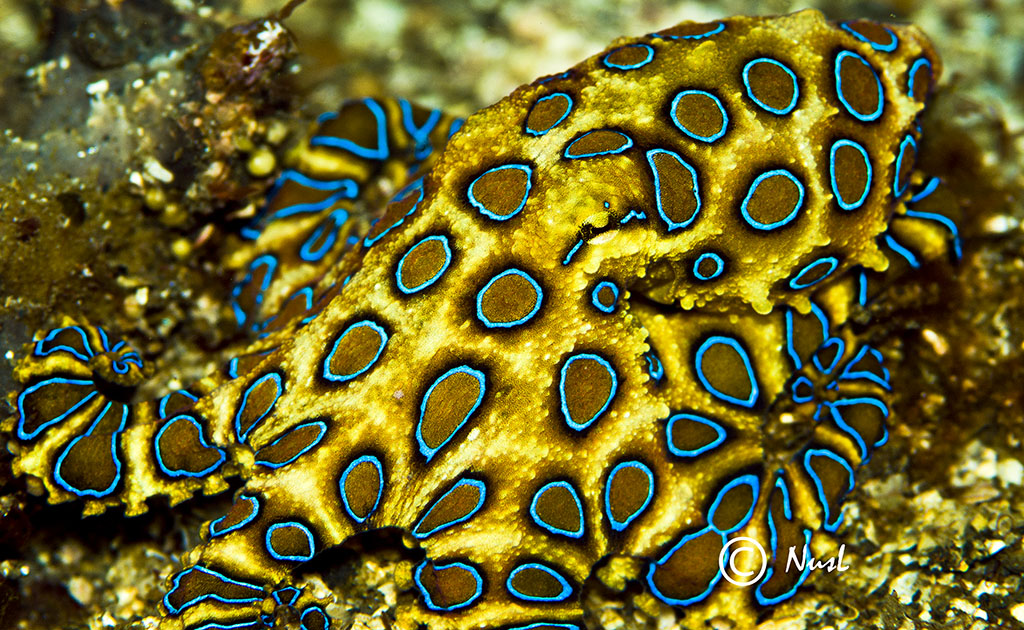

The blue-ringed octopuses (genus Hapalochlaena) are three (or perhaps four) octopus species that live in tide pools and coral reefs in the Pacific and Indian Oceans, from Japan to Australia (mainly around southern New South Wales and South Australia, and northern Western Australia). They are recognized as some of the world's most dangerous marine animals. Despite their small size and relatively docile nature, they can prove dangerous to humans. They can be recognized by their characteristic blue and black rings and yellowish skin. When the octopus is agitated, the brown patches darken dramatically, and iridescent blue rings or clumps of rings appear and pulsate within the maculae. Typically, 50–60 blue rings cover the dorsal and lateral surfaces of the mantle. They hunt small crabs, hermit crabs, and shrimp, and may bite attackers, including humans, if provoked. An individual blue-ringed octopus tends to use its dermal chromatophore cells to camouflage itself until provoked, at which point it quickly changes color, becoming bright yellow with blue rings or lines. The blue-ringed octopus spends much of its life hiding in crevices. Like all octopodes, it can change its shape easily, which helps it to squeeze into crevices much smaller than itself. This helps safeguard the octopus from predators and it may even pile up rocks outside the entrance to its lair. In common with other octopodes, the blue-ringed octopus swims by expelling water from its hyponome (funnel) in a form of jet propulsion. If the blue-ringed octopus loses one of its eight arms, it can regenerate it (grow it back) within six weeks The blue-ringed octopus diet typically consists of small crabs and shrimp, but they may also feed on fish if they can catch them. The blue-ringed octopus pounces on its prey, seizing it with its arms and pulling it towards its mouth. It uses its horny beak to pierce through the tough exoskeleton, releasing its venom. The venom paralyzes the muscles required for breathing and movement, which effectively kills the prey. The mating ritual for the blue-ringed octopus begins when a male approaches a female and begins to caress her with his modified arm, the hectocotylus. A male mates with a female by grabbing her, which sometimes completely obscures the female's vision, then transferring sperm packets by inserting his hectocotylus into her mantle cavity repeatedly. Mating continues until the female has had enough, and in at least one species the female has to remove the over-enthusiastic male by force. Males will attempt copulation with members of their own species regardless of sex or size, but interactions between males are most often shorter in duration and end with the mounting octopus withdrawing the hectocotylus without packet insertion or struggle. Blue-ringed octopus females lay only one clutch of about 50 eggs in their lifetimes towards the end of autumn. Eggs are laid then incubated underneath the female's arms for about six months, and during this process she does not eat. After the eggs hatch, the female dies, and the new offspring will reach maturity and be able to mate by the next year. The blue-ringed octopus is 12 to 20 cm (5 to 8 in), but its venom is powerful enough to kill humans. No blue-ringed octopus antivenom is available yet, making it one of the deadliest reef inhabitants in the ocean. The octopus produces venom containing tetrodotoxin, histamine, tryptamine, octopamine, taurine, acetylcholine, and dopamine. The major neurotoxin component of the blue-ringed octopus is a venom that was originally known as maculotoxinbut was later found to be identical to tetrodotoxin, a neurotoxin also found in pufferfish and some poison dart frogs that is 1 200 times more toxic than cyanide. Tetrodotoxin blocks sodium channels, causing motor paralysis and respiratory arrestwithin minutes of exposure, leading to cardiac arrest due to a lack of oxygen. The toxin is produced by bacteria in the salivary glands of the octopus. Their venom can result in nausea, respiratory arrest, heart failure, severe and sometimes total paralysis and blindness and can lead to death within minutes if not treated. Death, if it occurs, is usually from suffocation due to lack of oxygen to the brain. Although its venom can be deadly, the octopus's first instinct is to flee. If the threat persists, the octopus will go into a defensive stance and show its blue rings. First aid treatment is pressure on the wound and artificial respiration once the paralysis has disabled the victim's respiratory muscles, which often occurs within minutes of being bitten. Tetrodotoxin causes severe and often total body paralysis; the victim remains conscious and alert in a manner similar to curare or pancuronium bromide. This effect, however, is temporary and will fade over a period of hours as the tetrodotoxin is metabolized and excreted by the body. It is thus essential that rescue breathing be continued without pause until the paralysis subsides and the victim regains the ability to breathe on their own. This is a daunting physical prospect for a single individual, but use of a bag valve mask respirator reduces fatigue to sustainable levels until help can arrive. Definitive hospital treatment involves placing the patient on a medical ventilator until the toxin is removed by the body. The symptoms vary in severity, with children being the most at risk because of their small body size. Because the venom primarily kills through paralysis, victims are frequently saved if artificial respiration is started and maintained before marked cyanosis and hypotension develop. Victims who survive the first 24 hours usually recover completely. Efforts should be continued even if the victim appears not to be responding. Tetrodotoxin envenomation can result in victims being fully aware of their surroundings but unable to breathe. Because of the paralysis that occurs, they have no way of signaling for help or any way of indicating distress. Respiratory support, together with reassurance, until medical assistance arrives ensures the victims will generally recover well. The blue-ringed octopus, despite its small size, carries enough venom to kill 26 adult humans within minutes. Their bites are tiny and often painless, with many victims not realizing they have been envenomated until respiratory depression and paralysis start to set in!

5 Comments

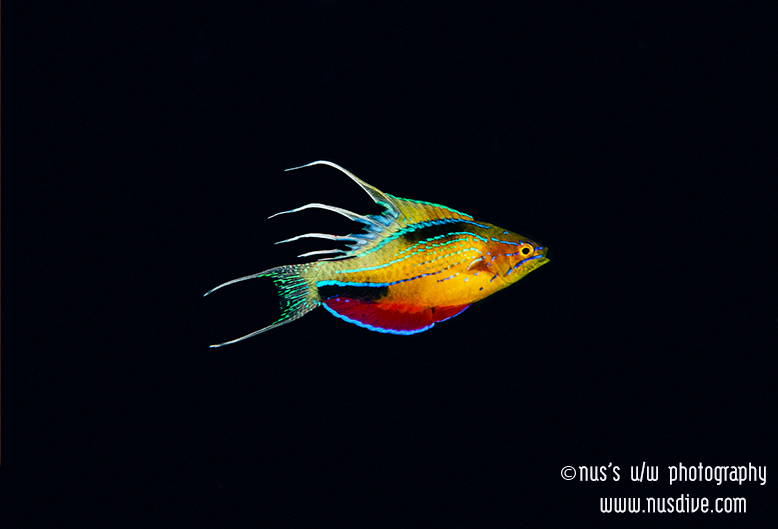

Paracheilinus nursalim belongs to a genus commonly known as flasher wrasses due to their vivid colouration, which is ‘flashed’ by the males during courtship displays. This colourful fish was first discovered in 2006 during a survey by Conservation International, and was formally described as a new species in 2008 The male Paracheilinus nursalim is usually dull reddish overall, fading to yellow on the belly and with a dusky grey area on the top of the back. There is also a black rectangular patch on the underside of the body, just before the tail. Each side of the male’s body has five narrow, red-brown stripes running along it, while a blue to purplish stripe runs below the eye, from the lip to the lower part of the operculum. The eyes of Paracheilinus nursalim are yellow. As in other members of the genus, males of Paracheilinus nursalim have long, tapering, filamentous extensions on around four to six of the rays of the dorsal fin. In this species, the dorsal fin is reddish-orange, with pinkish-red fin rays, while the pelvic fins, tail fin and broad anal fin are largely reddish. The tail fin of the male Paracheilinus nursalim has unusually long, trailing, filamentous extensions. During courtship, the male Paracheilinus nursalim undergoes a dramatic colour change, becoming orange overall and fading to whitish or pink on the upper side of the body. The conspicuous dark patch near the tail develops a bright blue stripe along its upper edge, and a second, less distinct dark patch becomes apparent on the upper back. In addition to the faint red stripes along the sides, the male Paracheilinus nursalim develops several bright blue stripes on the body and head, including one along the base of the dorsal fin . The dorsal fin of the male Paracheilinus nursalim turns yellowish to pinkish-white and has a sky blue margin during courtship, while the anal fin and pelvic fins become wine red, with a blue edge to the anal fin. The tail becomes translucent, with blue speckling and with pinkish-white filaments, and the pectoral fins turn a translucent yellowish colour . In contrast to the male, the female Paracheilinus nursalim is largely pinkish-red with yellow mottling, and has a series of yellow blotches along the base of the dorsal fin. Each side of the female’s body has four to five bluish or violet stripes, with irregular rows of blue or violet spots in between. Two blue to violet stripes extend backwards from the eye, and the female also has a light blue line running below the eye to the side of the breast. The dorsal fin and tail fin of the female Paracheilinus nursalim are yellowish with narrow blue bands and spots, while the anal fin is red with blue spots and the pelvic fins are whitish to pink. Paracheilinus nursalim is most easily distinguished from other members of its genus by the dark patches on the back and near the tail of the adult male, which are not present in other species. Paracheilinus nursalim is known only from the western central Pacific Ocean, where it occurs around Bird’s Head Peninsula in western New Guinea, Indonesia . It has been recorded from southeast Misool in the Raja Ampat group of islands, south-eastwards to Triton Bay and also now found in Ambon Bay, Maluku. |

AuthorNus's Blog Archives

May 2015

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed